if(!require(tidymodels)) install.packages("tidymodels")

if(!require(dplyr)) install.packages("dplyr")

if(!require(ggplot2)) install.packages("ggplot2")Tidymodels for omics data: Part 4

Pre-amble

In Part 1 of this series we described how to download TCGA data for breast cancers and manipulated them using a combination of tidybulk and dplyr to retain a set of expressed, variable genes. There are a set of packages that we will need for this Part 4:-

You will need the processed data from the Part one of this series and the code to download this is:-

### get the saved RDS

dir.create("raw_data", showWarnings = FALSE)

if(!file.exists("raw_data/brca_train_tidy.rds")) download.file("https://github.com/markdunning/markdunning.github.com/raw/refs/heads/master/posts/2025_11_06_tidymodels_TCGA_part1/brca_train_tidy.rds", destfile = "raw_data/brca_train_tidy.rds")

if(!file.exists("raw_data/brca_test_tidy.rds")) download.file("https://github.com/markdunning/markdunning.github.com/raw/refs/heads/master/posts/2025_11_06_tidymodels_TCGA_part1/brca_test_tidy.rds", destfile = "raw_data/brca_test_tidy.rds")The main purpose of this Part of the series is to learn how to optimise the models we created in Part 3a to predict Estrogen Receptor (ER) status from gene expression as measured by bulk RNA-seq. First we will load the pre-prepared tidy data.

brca_train_tidy <- readRDS("raw_data/brca_train_tidy.rds")

brca_test_tidy <- readRDS("raw_data/brca_test_tidy.rds")Let’s proceed by picking genes with an absolute correlation < 0.7 with ESR1 as our possible predictors. This is because we found ESR1 was too strong a predictor so we only required simple models if this gene was included.

library(dplyr)

kept_genes <- brca_train_tidy %>%

select(CLEC3A:BRINP2) %>%

cor() %>%

data.frame() %>%

tibble::rownames_to_column("Cor_with_Gene") %>%

select(ESR1, Cor_with_Gene) %>% #

filter(abs(ESR1) <0.7) %>%

pull(Cor_with_Gene)Now we restrict our data to just these genes, and the Estrogen Receptor status (renamed to ER for convenience). We will also create some ID rows in the data, which will be helpful in a short while.

er_train <- brca_train_tidy %>%

select(all_of(kept_genes), ER = er_status_by_ihc) %>%

mutate(ER = as.factor(ER)) %>%

mutate(ID = paste0("Training_", row_number())) %>%

relocate(ID)

er_test <- brca_test_tidy %>%

select(all_of(kept_genes), ER = er_status_by_ihc) %>%

mutate(ER = as.factor(ER)) %>%

mutate(ID = paste0("Training_", row_number())) %>%

relocate(ID)In Part 3a we introduced some machine learning methods that relied on hyperparameters in order to be run. This included logistic regression using glmnet that can “shrink” the influence of features in our data. The amount of shrinkage is controlled by the arguments penalty (also known as \(\lambda\)) and mixture (aka \(\alpha\)) in the tidymodels specification.

We just set these to some arbitrary, fixed values. So, the questions are: How can we choose the “best” values for these parameters without endless trial and error, and what data should we base that decision on?

Way back in Part 1 we split a TCGA breast cancer dataset into training and testing portions that were completely independent. The roles of these two portions are strictly defined:

Training Dataset: Used only to estimate the internal coefficients of our model and create the final fit. In our example of a logsitic regression, this would be the amount to which each gene affects the log-odds of a particular sample being ER

Positive.Testing Dataset: Used only for the final, independent validation of the model’s performance on completely unseen data.

Neither of these is appropriate for tuning. You might think the training data would be a good choice, but using it directly to pick the hyperparameters that would make our model overfit. It would be optimised for the training data and potentially perform poorly on the test set or other data.

So the solution is to create some new, temporary validation sets, based on our original training data, solely for the purpose of identifying (or “tuning”) the best hyperparameters. This technique is known as Cross-Validation (CV).

The purpose of tuning our models is really just that: fine-tuning to get the absolute best performance. It will not suddenly elevate performance metrics (like ROC AUC or Accuracy) from around 0.6 to 0.9 for example. Tuning should only be used in circumstances where you are already satisfied with the fundamental performance of your model and just require some minor, incremental adjustments. The performance gains from tuning are typically small.

That is to say that you should consider other choices of model, and even the fundamental data processing and feature engineering first, before trying to “tune” a model that is performing sub-par.

The greatest performance gains come from better data and model choice; tuning only optimizes the model you already have.

Cross-Validation

K-fold cross-validation (which tidymodels refers to as V-fold cross-validation) splits data into v equally-sized partitions to be used to tune hyper-parameters. As before, we need to make sure there is an equal representation of ER Positive and Negative as this is the variable we are trying to predict.

library(tidymodels)

## set a seed for reproducibility

set.seed(42)

er_folds <- er_train %>%

vfold_cv(v = 10,

strata = ER)Each of our v splits comprises a training and testing set, which can be accessed using the same training and testing functions from before.

er_folds$splits[[1]]<Analysis/Assess/Total>

<761/86/847>er_folds$splits[[1]] %>% training() %>%

slice_head(n = 10) %>%

select(1:5) ID CLEC3A SCGB2A2 CPB1 GSTM1

1 Training_1 5.130258 7.531285 7.361903 2.654743

2 Training_2 10.880983 14.974967 5.176676 7.004891

3 Training_3 1.974253 10.748514 4.059635 7.631561

4 Training_4 5.962898 12.580000 4.015388 12.110432

5 Training_5 2.717920 6.267474 1.974253 10.090312

6 Training_6 2.614033 4.950619 3.224804 1.974253

7 Training_7 2.622193 6.071904 3.078798 6.565902

8 Training_8 1.974253 5.501218 6.867097 9.812725

9 Training_9 2.685000 1.974253 1.974253 9.618968

10 Training_10 7.775900 17.372097 3.203721 7.853590er_folds$splits[[1]] %>% testing() %>%

slice_head(n = 10) %>%

select(1:5) ID CLEC3A SCGB2A2 CPB1 GSTM1

1 Training_11 2.925978 4.060384 3.570125 2.925978

2 Training_19 1.974253 9.958888 3.742617 5.993970

3 Training_20 1.974253 5.108298 2.799514 6.339706

4 Training_21 2.875813 10.638139 5.942479 12.452599

5 Training_22 1.974253 1.974253 8.276546 1.974253

6 Training_61 1.974253 3.557730 3.961746 11.389608

7 Training_68 3.391029 12.108652 8.519248 1.974253

8 Training_74 7.401455 13.309164 11.950340 8.095732

9 Training_77 4.371477 3.311226 3.456977 6.150631

10 Training_85 2.788086 10.734562 3.711402 7.437853With the same reasoning as creating our initial training and testing set, none of the samples included in the training set at each split is found in the corresponding testing set.

## intersect is a base R for function for finding elements in common between vectors

## intersect(c("A,"B","C"),c("B","D","E"))

intersect(training(er_folds$splits[[1]])$ID, testing(er_folds$splits[[1]])$ID)character(0)Model specifiction and recipe

Now when we create our model specification we declare that penalty and mixture are going to be tuned. Our “recipe” uses the same formula as before, but need to be careful as we introduce an ID column into the data. The workflow is also created at this stage.

lasso_spec_tune <- logistic_reg(

penalty = tune(), #Penalty (lambda): Use tune() to test different shrinkage strengths.

# Mixture (alpha): Use tune() to test the balance between Lasso (1) and Ridge (0) regularization, defining the Elastic Net.

mixture = tune()

) %>%

set_engine("glmnet") %>%

set_mode("classification")

er_recipe_multigene <- recipe(ER ~ ., data = er_train) %>%

update_role(ID, new_role = "ID") %>%

step_normalize(all_numeric_predictors())

## Need to say that our ID column is an identifier - not something to be included in the model

elastic_net_wflow <- workflow() %>%

add_recipe(er_recipe_multigene) %>%

add_model(lasso_spec_tune)Setup a grid for tuning

Unfortunately there are an infinite number of possibilities that both these arguments can take and we clearly cannot test them all. What we do instead is try and explore the full range of values, and find roughly the region where the optimal values are located. In practical terms this is often perfectly adequate.

Infrastructure for tuning parameters is supporedt by the dials and tune packages which are both part of the tidymodels eco-system. i.e. they get installed and loaded when you install and load tidymodels.

There are a couple of convenient helper functions penalty and mixture that will create templates for choosing values for tuning. We then have to create a grid of values that we want to test. This is simply a data frame (/tibble) containing combinations of penalty and mixture and can be created with the grid_regular function. This function will ensure that the full range of values is tested. In other words that the maximum and minimum values are included in the search. With the levels argument we can control how finely we split the ranges.

Another option is to use grid_random to create a random set of combinations of the parameters. Instead of levels we say how many combinations we want in total using size.

penalty_range <- penalty(range = c(-5, 0)) # use helper function to define range of penalty values

mixture_range <- mixture() # use helper function to define a range of mixture values

elastic_net_grid_regular <- grid_regular(

penalty_range,

mixture_range,

levels = c(penalty = 5, mixture = 3) # Test 5 penalty values x 3 mixture values = 15 combinations

)

elastic_net_grid_random <- grid_random(

penalty_range,

mixture_range,

size = 15

)With the setup we have just created there are 15 different models to be fit (one model for each combination in our grid), and the 10-fold strategy we defined with vfolds_cv means we have to fit each of these 15 models 10 times. In total we have 150 models, and for each we want to assess the performance of each. This is quite a lot of work! Fortunately we can do this quite efficiently with tidymodels and get an output that we can assess. The tune_grid function will use the cross-validation strategy defined with vfolds_cv, a grid structure and compute performance metrics for your workflow.

Inspect tuning results

elastic_net_tune_res <- tune_grid(

elastic_net_wflow,

resamples = er_folds,

grid = elastic_net_grid_regular,

metrics = metric_set(accuracy, specificity, sensitivity, roc_auc)

)The actual object itself is not particularly informative when printed:-

elastic_net_tune_res # Tuning results

# 10-fold cross-validation using stratification

# A tibble: 10 × 4

splits id .metrics .notes

<list> <chr> <list> <list>

1 <split [761/86]> Fold01 <tibble [60 × 6]> <tibble [0 × 3]>

2 <split [761/86]> Fold02 <tibble [60 × 6]> <tibble [0 × 3]>

3 <split [761/86]> Fold03 <tibble [60 × 6]> <tibble [0 × 3]>

4 <split [762/85]> Fold04 <tibble [60 × 6]> <tibble [0 × 3]>

5 <split [763/84]> Fold05 <tibble [60 × 6]> <tibble [0 × 3]>

6 <split [763/84]> Fold06 <tibble [60 × 6]> <tibble [0 × 3]>

7 <split [763/84]> Fold07 <tibble [60 × 6]> <tibble [0 × 3]>

8 <split [763/84]> Fold08 <tibble [60 × 6]> <tibble [0 × 3]>

9 <split [763/84]> Fold09 <tibble [60 × 6]> <tibble [0 × 3]>

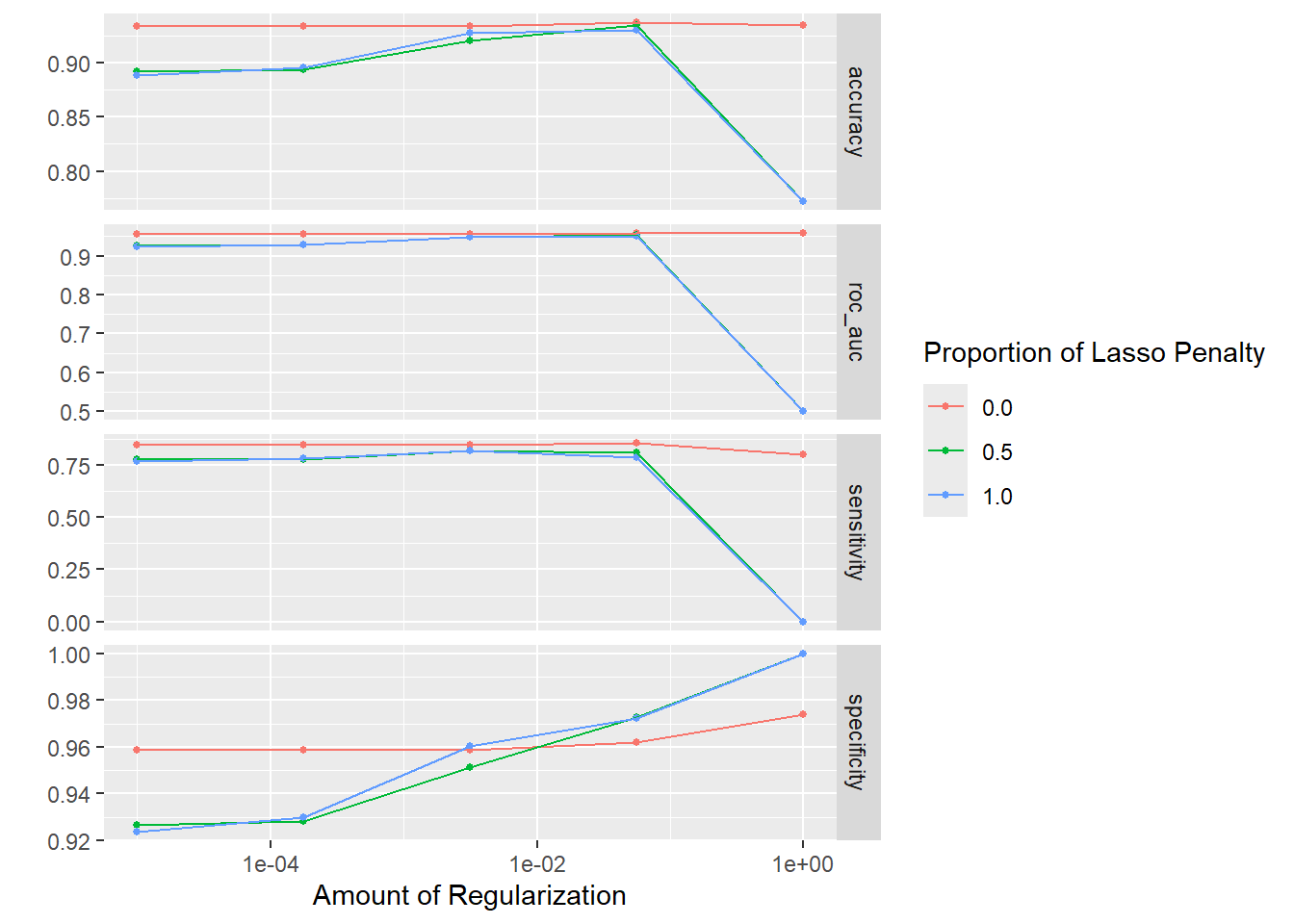

10 <split [763/84]> Fold10 <tibble [60 × 6]> <tibble [0 × 3]>There is however a handy plotting method that will give a quick overview of the metrics achieved for different runs of the model. On the whole, it looks like a mixture of 0 is best with little difference as the penalty (amount of regularization) changes. Recall that a mixture of 0 corresponds to Ridge, as opposed to Lasso meaning that the final model that we fit will not set any coefficients to zero.

elastic_net_tune_res %>% autoplot

We can also request details of the “best” models according to a particular metric. ROC AUC is generally a good idea as it balances the specificity and sensitivity. The metrics shown in the table are averaged over the v-folds, which is 10 in our case.

show_best(elastic_net_tune_res, metric = "roc_auc", n = 5)# A tibble: 5 × 8

penalty mixture .metric .estimator mean n std_err .config

<dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <chr>

1 0.0562 0 roc_auc binary 0.959 10 0.0103 Preprocessor1_Model04

2 1 0 roc_auc binary 0.958 10 0.00964 Preprocessor1_Model05

3 0.00001 0 roc_auc binary 0.956 10 0.0107 Preprocessor1_Model01

4 0.000178 0 roc_auc binary 0.956 10 0.0107 Preprocessor1_Model02

5 0.00316 0 roc_auc binary 0.956 10 0.0107 Preprocessor1_Model03If we want to concentrate on a specific measure (such as sensitivity), we can look at that too.

show_best(elastic_net_tune_res, metric = "sensitivity", n=5)# A tibble: 5 × 8

penalty mixture .metric .estimator mean n std_err .config

<dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <chr>

1 0.0562 0 sensitivity binary 0.855 10 0.0312 Preprocessor1_Mod…

2 0.00001 0 sensitivity binary 0.849 10 0.0348 Preprocessor1_Mod…

3 0.000178 0 sensitivity binary 0.849 10 0.0348 Preprocessor1_Mod…

4 0.00316 0 sensitivity binary 0.849 10 0.0348 Preprocessor1_Mod…

5 0.00316 1 sensitivity binary 0.818 10 0.0346 Preprocessor1_Mod…Create final model and fit

Once we are happy, we can save the details of the best model.

best_params <- select_best(elastic_net_tune_res, metric = "roc_auc")

best_params# A tibble: 1 × 3

penalty mixture .config

<dbl> <dbl> <chr>

1 0.0562 0 Preprocessor1_Model04And the choice of parameters can be fed back to our workflow. Our workflow up to this point only has placeholders for the mixture and penalty.

elastic_net_wflow══ Workflow ════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

Preprocessor: Recipe

Model: logistic_reg()

── Preprocessor ────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

1 Recipe Step

• step_normalize()

── Model ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Logistic Regression Model Specification (classification)

Main Arguments:

penalty = tune()

mixture = tune()

Computational engine: glmnet With finalize_workflow these values get updated according to our final choices.

final_wflow <- elastic_net_wflow %>%

finalize_workflow(best_params)

final_wflow══ Workflow ════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

Preprocessor: Recipe

Model: logistic_reg()

── Preprocessor ────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

1 Recipe Step

• step_normalize()

── Model ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Logistic Regression Model Specification (classification)

Main Arguments:

penalty = 0.0562341325190349

mixture = 0

Computational engine: glmnet Remember that the purpose of tuning was to find an optimal set of hyperparameters, and we did that using a newly-created set of cross-validation subsets. We still need to fit, and create, the final model using those paramaters that we chose. This still needs to be performed on our entire training dataset.

final_model_fit <- fit(final_wflow, data = er_train)

final_model_fit %>% tidy# A tibble: 246 × 3

term estimate penalty

<chr> <dbl> <dbl>

1 (Intercept) 2.71 0.0562

2 CLEC3A 0.0756 0.0562

3 SCGB2A2 -0.0580 0.0562

4 CPB1 0.0248 0.0562

5 GSTM1 -0.204 0.0562

6 TFF1 0.116 0.0562

7 S100A7 -0.0151 0.0562

8 SCGB1D2 0.00630 0.0562

9 KCNJ3 0.0352 0.0562

10 LINC00993 -0.0425 0.0562

# ℹ 236 more rowsFinally we can make predictions using our testing data which hasn’t been used in any of the previous steps and assess the metrics

class_metrics <- metric_set(accuracy, sensitivity, specificity)

select(er_test ,ER) %>%

bind_cols(predict(final_model_fit, new_data = er_test)) %>%

class_metrics(truth = ER, estimate = .pred_class)# A tibble: 3 × 3

.metric .estimator .estimate

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 accuracy binary 0.925

2 sensitivity binary 0.918

3 specificity binary 0.927The accuracy, sensitivity and specificity from our previous logistic regression were 0.920, 0.857 and 0.939 respectively so it looks like we are improving our sensitivity at the cost of a slight decrease in specificity. After tuning we have ended up with a model that is doing better at predicting both positive and negative cases .🎉

Training for Random Forests

We’ll now walk through an example of tuning a random forest, and hopefully you will see that the process is roughly the same. A useful starting point is the show_model_info function that will give us plenty of information about using a particular machine learning methods, the “engines” that can be used and what arguments can be set.

show_model_info("rand_forest")Information for `rand_forest`

modes: unknown, classification, regression, censored regression

engines:

classification: randomForest, ranger¹, spark

regression: randomForest, ranger¹, spark

¹The model can use case weights.

arguments:

ranger:

mtry --> mtry

trees --> num.trees

min_n --> min.node.size

randomForest:

mtry --> mtry

trees --> ntree

min_n --> nodesize

spark:

mtry --> feature_subset_strategy

trees --> num_trees

min_n --> min_instances_per_node

fit modules:

engine mode

ranger classification

ranger regression

randomForest classification

randomForest regression

spark classification

spark regression

prediction modules:

mode engine methods

classification randomForest class, prob, raw

classification ranger class, conf_int, prob, raw

classification spark class, prob

regression randomForest numeric, raw

regression ranger conf_int, numeric, raw

regression spark numericIn the output it lists mtry, trees and min_n all as arguments that can be tuned. These arguments control the diversity (mtry), complexity (min_n) and number of trees used for consensus voting (trees). The purpose of tuning these parameters is to give a selection of tree with enough complexity and diversity in our training data without overfitting. The particular optimal combination of these values with vary from dataset to dataset, and hence why they need to be tuned. A random forest specification with hyper-parameters to be tuned can be created as follows:-

rf_spec_tune <- rand_forest(

trees=tune(),

mtry = tune(),

min_n = tune()) %>%

set_engine("ranger", importance = "permutation") %>%

set_mode("classification")and now create the workflow

rf_workflow <- workflow() %>%

add_model(rf_spec_tune) %>%

add_recipe(er_recipe_multigene)To define the grid for searching we can again make use of the dials package that had pre-defined notions of what values the mtry, trees and min_n should contain and stop us accidentally trying to create a model with invalid parameters values. This would be useful in a situation where we were trying more advance methods of grid searching, or even using random grids.

mtry_range <- mtry(range = c(5,50))

tree_range <- trees(range = c(500,2000))

minn_range <- min_n(range = c(5,50))

rf_grid <- grid_regular(

mtry_range,

tree_range,

minn_range,

levels = c(mtry = 5, trees = 3, min_n = 3)

)

rf_grid# A tibble: 45 × 3

mtry trees min_n

<int> <int> <int>

1 5 500 5

2 16 500 5

3 27 500 5

4 38 500 5

5 50 500 5

6 5 1250 5

7 16 1250 5

8 27 1250 5

9 38 1250 5

10 50 1250 5

# ℹ 35 more rowsWe are now ready to do the tuning, which without any further modifications to the code would take a lot longer. Fortunately, I have Dr. Lewis Quayle to thank for some code on his post on tidymodels to configure tidymodels to use multiple CPU cores on your computer where available.

We can run the code in parallel because the tuning process is inherently an example of what was called “embarrassingly parallel” back in the day (people sometimes prefer “Pleasingly parallel” nowadays). In other words, the training / testing occurring at each fold in our workflow is completely independant and can therefore be run at the same time if possible rather than waiting for the previous fold to finish.

## setting a seed required for reproducibility

set.seed(42)

# register a parallel back-end

future::plan(future::multisession(), workers = parallel::detectCores() - 1)

rf_tune_res <- tune_grid(

rf_workflow,

resamples = er_folds,

grid = rf_grid,

metrics = metric_set(accuracy, specificity, sensitivity, roc_auc)

)

saveRDS(rf_tune_res, "rf_tune_res.rds")If this takes too long you can download the resulting object with the following:-

if(!file.exists("rf_tune_res.rds")) download.file("https://github.com/markdunning/markdunning.github.com/raw/refs/heads/master/posts/2025_11_22_tidymodels_TCGA_part4/rf_tune_res.rds")As before, we can plot to get a quick overview.

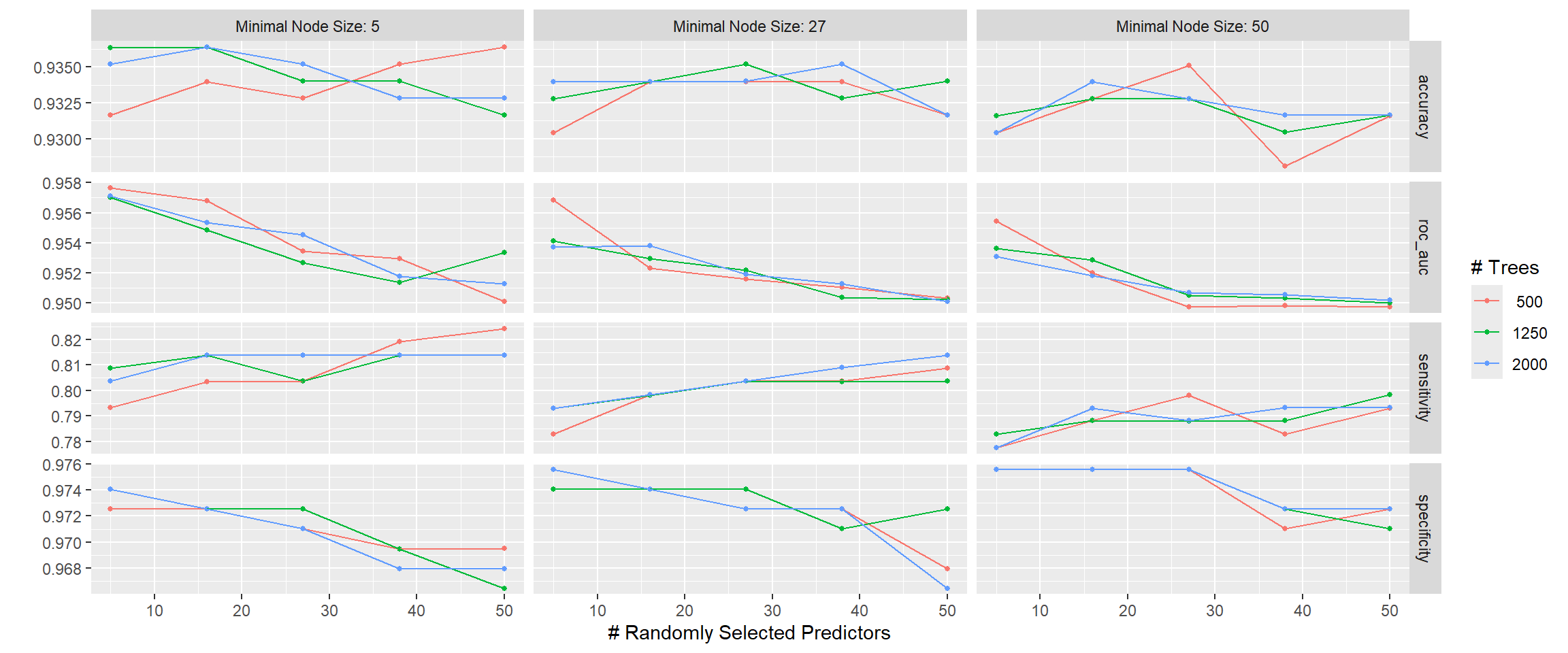

rf_tune_res %>% autoplot()

The plot chooses informative labels where “Minimal Node Size” = min_n and “# Randomly Selected Predictors” = mtry. If we wish to focus on Area Under the Curve (roc_auc) the best combination looks to be lower min_n and mtry.

show_best(elastic_net_tune_res, metric = "roc_auc")# A tibble: 5 × 8

penalty mixture .metric .estimator mean n std_err .config

<dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <chr>

1 0.0562 0 roc_auc binary 0.959 10 0.0103 Preprocessor1_Model04

2 1 0 roc_auc binary 0.958 10 0.00964 Preprocessor1_Model05

3 0.00001 0 roc_auc binary 0.956 10 0.0107 Preprocessor1_Model01

4 0.000178 0 roc_auc binary 0.956 10 0.0107 Preprocessor1_Model02

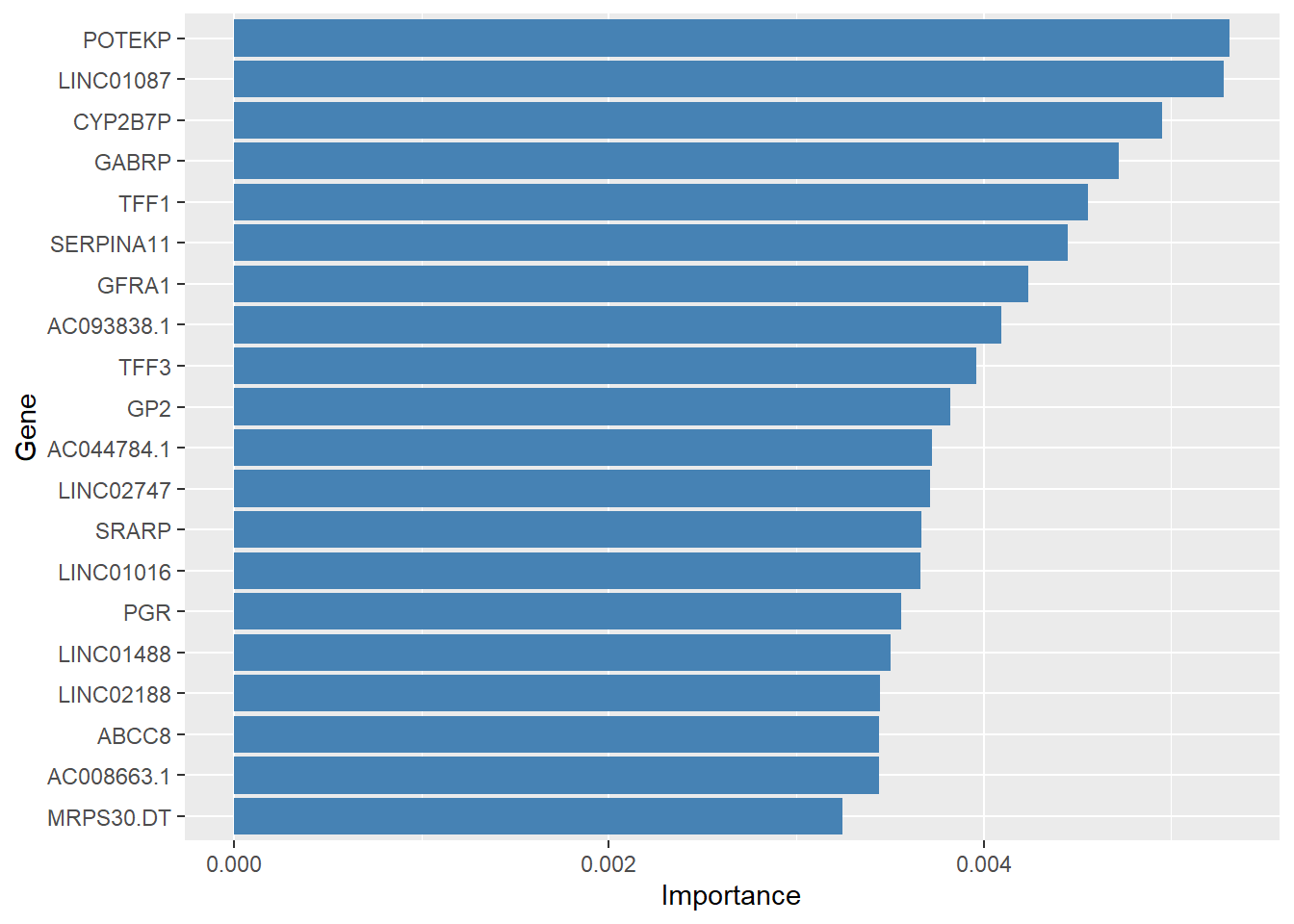

5 0.00316 0 roc_auc binary 0.956 10 0.0107 Preprocessor1_Model03best_params <- select_best(rf_tune_res, metric = "roc_auc")And now we can create the final model and check the importance of the features

rf_final_workflow <- rf_workflow %>%

finalize_workflow(best_params)

rf_final_fit <- rf_final_workflow %>%

fit(er_train)

importance_df <- pull_workflow_fit(rf_final_fit)$fit$variable.importance %>%

enframe(name = "term", value = "Importance") %>%

arrange(desc(Importance))and we can make a simple bar plot if we wish

importance_df %>%

## pick the top 20

slice_max(Importance, n = 20) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Importance, y = forcats::fct_reorder(term, Importance))) + geom_col(fill = "steelblue") + ylab("Gene") + xlab("Importance")

and the final predictions and evaluation follow a pattern that is hopefully familiar by now

rf_final_fit %>%

predict(new_data = er_test) %>%

bind_cols(select(er_test, ER)) %>%

class_metrics(truth = ER, estimate = .pred_class)# A tibble: 3 × 3

.metric .estimator .estimate

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 accuracy binary 0.925

2 sensitivity binary 0.898

3 specificity binary 0.933Summary

This concludes the end of this little series on using tidymodels for classification of omics data. I hope that I have covered the main principles of the tidymodels eco-system. Just looking through the code I can see a lot of places where the code is reused, which is good for readability and extend-ability. Even though I have not covered all the possible classification methods, it should be possible with relative ease (that is relative to coding everything from scratch) to translate what we have covered here to other methods. This is real advantage of tidymodels in that most of our time should be spent interpreting and refining models than having to code everything by-hand. I haven’t even covered the use of regression vs classification (that is, predicting a numeric rather than categorical outcome) and again this should be within your reach now by using set_mode("regression") instead of classification in the models covered here. On the parsnip site (the part of tidymodels that it is responsible for model specification) you will searchable page index of supported models

If you are looking to practice your new machine learning skills, I also recommend Kaggle as a source of datasets and inspiration, as the notebooks to analyse the datasets are also made freely available. Once you find a dataset of interest, you can filter for notebooks that use R (or Python if you’re feeling adventurous). N.B. you will need to sign-up for a free account.

There is also a “Tidy Tuesday” project that releases an interesting, curated, dataset into the community every week. Although not all will be suitable for machine learning, you will be able to practice your data manipulation and visualistion skills.

There is even an R package that will help with downloading

install.packages("tidyTuesdayR")Of course it would be remiss of me not to mention AI and deep learning methods that are increasingly being used in research. Whilst these are more complex methods, the core principles of training / testing and tuning are still highly applicable. Furthermore, these methods are still completely dependant on having appropriately filtered and cleaned data as a starting point. Although Python is probably the market leader for AI, R actually has interfaces to keras and tensorflow (two of the most popular implementations). There is no need to abandon R just yet 😉